The Maya calendar may seem less complicated if one considers our own Gregorian calendar system first. If a date was given as Thanksgiving Day, Thursday, November 23, 1997 in the Age of Aquarius, and during President Clinton's Presidency we would for the most part understand what was meant even though we might not know where the words "Thursday" and "November" came from. It may also help to recall that weekdays go through a cycle that has nothing to do with astronomy or the position of the sun and earth and that 1997 really means 1 period of 1000 years, plus 9 periods of 100 years, plus 9 periods of 10 years plus 7 periods of 1 year.I do recommend visiting this site to learn more about the Calendar system as well as MesoAmerica.

Tzolk'in

The tzolk'in (in modern Maya orthography; also commonly written tzolkin) is the name commonly employed by Mayanist researchers for the Maya Sacred Round or 260-day calendar. The word tzolk'in is a neologism coined in Yucatec Maya, to mean "count of days" (Coe 1992). The various names of this calendar as used by Precolumbian Maya peoples are still debated by scholars. The Aztec calendar equivalent was called Tonalpohualli, in the Nahuatl language.

The tzolk'in calendar combines twenty day names with the thirteen numbers of the trecena cycle to produce 260 unique days. It is used to determine the time of religious and ceremonial events and for divination. Each successive day is numbered from 1 up to 13 and then starting again at 1. Separately from this, each day is given a name in sequence from a list of 20 day names:

Some systems started the count with 1 Imix', followed by 2 Ik', 3 Ak'b'al, etc. up to 13 B'en. The trecena day numbers then start again at 1 while the named-day sequence continues onwards, so the next days in the sequence are 1 Ix, 2 Men, 3 K'ib', 4 Kab'an, 5 Etz'nab', 6 Kawoq, and 7 Ajau. With all twenty named days used, these now began to repeat the cycle while the number sequence continues, so the next day after 7 Ajaw is 8 Imix'. The repetition of these interlocking 13- and 20-day cycles therefore takes 260 days to complete (that is, for every possible combination of number/named day to occur once).

The exact origin of the Tzolk'in is not known, but there are several theories. One theory is that the calendar came from mathematical operations based on the numbers thirteen and twenty, which were important numbers to the Maya. The numbers multiplied together equal 260. Another theory is that the 260-day period came from the length of human pregnancy. This is close to the average number of days between the first missed menstrual period and birth, unlike Naegele's rule which is 40 weeks (280 days) between the last menstrual period and birth. It is postulated that midwives originally developed the calendar to predict babies' expected birth dates.

A third theory comes from understanding of astronomy, geography and paleontology. The mesoamerican calendar probably originated with the Olmecs, and a settlement existed at Izapa, in southeast Chiapas Mexico, before 1200 BC. There, at a latitude of about 15° N, the Sun passes through zenith twice a year, and there are 260 days between zenithal passages, and gnomons (used generally for observing the path of the Sun and in particular zenithal passages), were found at this and other sites. The sacred almanac may well have been set in motion on August 13, 1359 BC, in Izapa. Vincent H. Malmström, a geographer who suggested this location and date, outlines his reasons:

(1) Astronomically, it lay at the only latitude in North America where a 260-day interval (the length of the "strange" sacred almanac used throughout the region in pre-Columbian times) can be measured between vertical sun positions -- an interval which happens to begin on the 13th of August -- the day the peoples of the Mesoamerica believed that the present world was created;

(2) Historically, it was the only site at this latitude which was old enough to have been the cradle of the sacred almanac, which at that time (1973) was thought to date to the 4th or 5th centuries B.C.; and (3) Geographically, it was the only site along the required parallel of latitude that lay in a tropical lowland ecological niche where such creatures as alligators, monkeys, and iguanas were native -- all of which were used as day-names in the sacred almanac.

Malmström also offers strong arguments against both of the former explanations.

A fourth theory is that the calendar is based on the crops. From planting to harvest is approximately 260 days.

Haab'

The Haab' was the Maya solar calendar made up of eighteen months of twenty days each plus a period of five days ("nameless days") at the end of the year known as Wayeb' (or Uayeb in 16th C. orthography). Bricker (1982) estimates that the Haab' was first used around 550 BC with the starting point of the winter solstice.

The Haab' month names are known today by their corresponding names in colonial-era Yukatek Maya, as transcribed by 16th century sources (in particular, Diego de Landa and books such as the Chilam Balam of Chumayel). Phonemic analyses of Haab' glyph names in pre-Columbian Maya inscriptions have demonstrated that the names for these twenty-day periods varied considerably from region to region and from period to period, reflecting differences in the base language(s) and usage in the Classic and Postclassic eras predating their recording by Spanish sources.

Each day in the Haab' calendar was identified by a day number in the month followed by the name of the month. Day numbers began with a glyph translated as the "seating of" a named month, which is usually regarded as day 0 of that month, although a minority treat it as day 20 of the month preceding the named month. In the latter case, the seating of Pop is day 5 of Wayeb'. For the majority, the first day of the year was 0 Pop (the seating of Pop). This was followed by 1 Pop, 2 Pop as far as 19 Pop then 0 Wo, 1 Wo and so on.

As a calendar for keeping track of the seasons, the Haab' was a bit inaccurate, since it treated the year as having exactly 365 days, and ignored the extra quarter day (approximately) in the actual tropical year. This meant that the seasons moved with respect to the calendar year by a quarter day each year, so that the calendar months named after particular seasons no longer corresponded to these seasons after a few centuries. The Haab' is equivalent to the wandering 365-day year of the ancient Egyptians.

Wayeb'

The five nameless days at the end of the calendar, called Wayeb', were thought to be a dangerous time. Foster (2002) writes "During Wayeb, portals between the mortal realm and the Underworld dissolved. No boundaries prevented the ill-intending deities from causing disasters." To ward off these evil spirits, the Maya had customs and rituals they practiced during Wayeb'. For example, people avoided leaving their houses or washing or combing their hair.

Calendar Round

Neither the Tzolk'in nor the Haab' system numbered the years. The combination of a Tzolk'in date and a Haab' date was enough to identify a date to most people's satisfaction, as such a combination did not occur again for another 52 years, above general life expectancy.

Because the two calendars were based on 260 days and 365 days respectively, the whole cycle would repeat itself every 52 Haab' years exactly. This period was known as a Calendar Round. The end of the Calendar Round was a period of unrest and bad luck among the Maya, as they waited in expectation to see if the gods would grant them another cycle of 52 years.

Long Count

Since Calendar Round dates can only distinguish in 18,980 days, equivalent to around 52 solar years, the cycle repeats roughly once each lifetime, and thus, a more refined method of dating was needed if history was to be recorded accurately. To measure dates, therefore, over periods longer than 52 years, Mesoamericans devised the Long Count calendar.

The Maya name for a day was k'in. Twenty of these k'ins are known as a winal or uinal. Eighteen winals make one tun. Twenty tuns are known as a k'atun. Twenty k'atuns make a b'ak'tun.

The Long Count calendar identifies a date by counting the number of days from the Mayan creation date 4 Ahaw, 8 Kumk'u (August 11, 3114 BC in the proleptic Gregorian calendar or September 6 in the Julian calendar). But instead of using a base-10 (decimal) scheme like Western numbering, the Long Count days were tallied in a modified base-20 scheme. Thus 0.0.0.1.5 is equal to 25, and 0.0.0.2.0 is equal to 40. As the winal unit resets after only counting to 18, the Long Count consistently uses base-20 only if the tun is considered the primary unit of measurement, not the k'in; with the k'in and winal units being the number of days in the tun. The Long Count 0.0.1.0.0 represents 360 days, rather than the 400 in a purely base-20 (vigesimal) count. There are also four rarely-used higher-order cycles: piktun, kalabtun, k'inchiltun, and alautun.

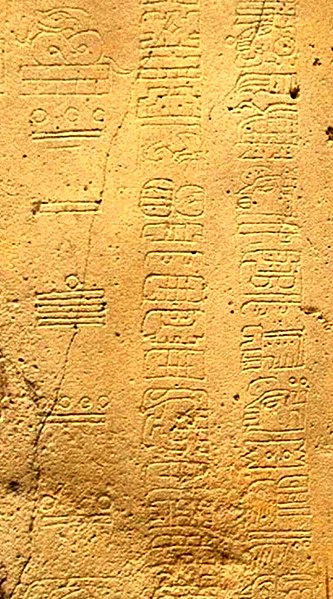

Since the Long Count dates are unambiguous, the Long Count was particularly well suited to use on monuments. The monumental inscriptions would not only include the 5 digits of the Long Count, but would also include the two tzolk'in characters followed by the two haab' characters.

The Mesoamerican Long Count calendar forms the basis for a New Age belief, first forecast by José Argüelles, that a cataclysm will take place on or about December 21, 2012, a forecast that mainstream Mayanist scholars consider a misinterpretation, yet is commonly referenced in pop-culture media as the 2012 problem.

For example, Sandra Noble, executive director of the Mesoamerican research organization FAMSI, notes that "[f]or the ancient Maya, it was a huge celebration to make it to the end of a whole cycle". However, she considers the portrayal of December 2012 as a doomsday or cosmic-shift event to be "a complete fabrication and a chance for a lot of people to cash in."

Venus Cycle

Another important calendar for the Maya was the Venus cycle. The Maya were skilled astronomers, and could calculate the Venus cycle with extreme accuracy. There are six pages in the Dresden Codex (one of the Maya codices) devoted to the accurate calculation of the heliacal rising of Venus. The Maya were able to achieve such accuracy by careful observation over many years.

There are various theories as to why Venus cycle was especially important for the Maya, including the belief that it was associated with war and used it to divine good times (called electional astrology) for coronations and war. Maya rulers planned for wars to begin when Venus rose. The Maya also possibly tracked other planets’ movements, including those of Mars, Mercury, and Jupiter.

I recommend visiting the Wikipedia site because they have the glyphs associated with Tzolk'in as well as the Mayan names for the different months, periods, etc.

_______________________

References:

Anonymous. 2009. "Maya calendar". Wikipedia. Posted: October 14, 2009. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_calendar

Callahan, Kevin L. 1997. "The Maya Calendar". Ancient Mesoamerican Civilizations. Posted: June 10, 1997. Available online: http://www.angelfire.com/ca/humanorigins/calendarsystem.html

Picture Credits:

The Mayan Calendar is from : http://www.geocities.com/wwwtimto/maya.html I also recommend you visit the site. Site maintainer is Tim To. Because it is a geocities site it will be taken down by Yahoo shortly. Hopefully, it will still exist at Internet Archive. It also appears that the site was last updated in 2007.

Long Calendar is from: Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_calendar

No comments:

Post a Comment