People do not like to be observed when they cause harm to others

The heated debate surrounding the German "state Trojan" software for the online monitoring of telecommunication between citizens shows that the concealed observation of our private decisions provokes public disapproval. However, as a recent experimental study has revealed, observing and being observed are integral components of our social repertoire. Human beings show a preference for social partners whose altruistic behaviour they have been able to confirm for themselves. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön and the University of Cologne have discovered that people select future social partners on the basis of their cooperative behaviour and not according to whether they punish the egoism of others. This finding is surprising as it shows that people identify particularly altruistic partners in this way and could benefit from their behaviour. Consequently, people conceal uncooperative behaviour. However, it remains a mystery as to why people would like to conceal occasions when they punish others for their self-interest, despite the fact that they have no sanctions to fear.

Cooperative behaviour is generally associated with personal disadvantage. Scientists have therefore long been unable to explain why, despite this, altruism exists in nature. However, altruistic behaviour can be successful if organisms improve their reputation through unselfish behaviour and can benefit from it at a later stage: those who give receive; but those who refuse to lend support cannot expect help in an emergency. Solidarity is also the outcome of social evolution in humans. However, altruism can only enhance an individual's reputation and prevail if the corresponding behaviour is known to others.

Thus, people behave more cooperatively when they are observed. Accordingly, as soon as they are aware that they are being observed, egoists try to conceal their behaviour and pretend to act cooperatively. The observer, in turn, would like to prevent this and tries to conceal his or her attention. The researchers from Cologne and Plön discovered this interaction with the help of public goods games, in which the participants could benefit from egoistic behaviour. Their experiments showed that external observers prefer people who show solidarity as future game partners. Moreover, they are willing to pay to conceal their observation of another player. The players were also willing to pay to conceal egoistic behaviour. "A kind of 'arms race' thus arises between the two parties. They both want to keep their intentions secret from the other," says Manfred Milinski from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology.

Interestingly, observers seldom select people who punish others for egoistic behaviour. In effect, such sanctions are an expression of altruistic behaviour, as they are associated with personal costs incurred for the general good. "A person who observes other people with a view to finding cooperative partners would be expected to take punishment behaviour into account. The finding that people do not use this information raises important new research questions," says Bettina Rockenbach from the University of Cologne.

The researchers also observed that people prefer to hide the fact that they have punished others for egoistic behaviour. This is also surprising as punishments can be justified in terms of concern for the general good. Despite this, people apparently fear for their reputation if they punish others severely for egoistic behaviour. This finding is all the more unexpected as the tests showed that observers do not attach any importance to this information.

The researchers analysed three variants of a public goods game in their study. In all three games, the participants were accompanied by an observer who, after 15 rounds of the game, could remove a random or specific player and play himself; the replacement of a specific player incurred a cost. The observer could also conceal which players he or she was observing at a cost. The players, in turn, could pay to ensure that the observer did not find out anything about a decision.

In the simple variant of the game, a group of four participants merely had to decide between uncooperative and cooperative behaviour. They were given an actual sum of money and could decide whether to pay part of it into a shared kitty or keep all of it for themselves. At the end of the round, the sum in the group kitty was doubled and distributed evenly among the participants. The more players that paid into the kitty, the more they all benefited from it - however, the egoists profited most at the cost of the altruists. Under these conditions, egoistic behaviour prevailed after a few repetitions of the game.

In contrast, altruistic behaviour could prove a successful strategy in the other two variants of the game. Each of the participants was able impose punishments on the other players upon completion of a round of the public goods game. The punishments were withdrawn from the account of the individual in question and he or she also had to contribute something for the punishment. In the third variant, having been informed about the contributions received and made by the potential recipient, each of the participants was able to make contributions to one of the other players and receive them from another depending on whether he or she had improved his reputation by paying into the group kitty.

______________

References:

EurekAlert. 2011. "Punishment of egoistic behavior is not rewarded". EurekAlert. Posted: November 14, 2011. Available online: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-11/m-po111411.php

Original publication:

"To qualify as a social partner, humans hide severe punishment, although their observed cooperativeness is decisive" Bettina Rockenbach, and Manfred Milinski

PNAS, November 08, 2011,vol. 108(45): 18307-18312 (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108996108)

Notes by a socio-cultural anthropologist in areas and topics that appeal to her.

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Archeologists Discover Huge Ancient Greek Commercial Area On Island of Sicily

The Greeks were not always in such dire financial straits as today. German archeologists have discovered a very large commercial area from the ancient Greek era during excavations on Sicily.

Led by Professor Dr. Martin Bentz, archeologists at the University of Bonn began unearthing one of Greek antiquity's largest craftsmen's quarters in the Greek colonial city of Selinunte (7th-3rd century B.C.) on the island of Sicily during two excavation campaigns in September 2010 and in the fall of 2011.

The project is conducted in collaboration with the Italian authorities and the German Archaeological Institute. Its goal is to study an area of daily life in ancient cities that has hitherto received little attention.

"To what extent the ancient Greeks already had something like 'commercial areas' has been a point of discussion in expert circles to this day," said Bonn archeologist Dr. Gabriel Zuchtriegel, a research associate who coordinates the Selinunte project together with Dr. Jon Albers from the Institut für Klassische Archäologie der Universität Bonn at the Chair of Prof. Dr. Martin Bentz. "A concentration of certain 'industries' and craftsmen in special districts does not only presuppose proactive planning; it is also based on a certain idea of how a city should best be organized -- from a practical as well as from a social and political point of view, e.g., who will be allowed to live and work where?" The University of Bonn excavations are now contributing to finding a new answer to such questions.

Huge kilns, used communally

Concentration in a certain city district applied primarily to potteries in Selinunte, which were massed on the edge of the settlement in the very shadow of the city wall. "Consequently, their smoke, stench and noise did not inconvenience the other inhabitants as much," explained Dr. Zuchtriegel. "At the same time, this allowed several craftsmen to use kilns and storage facilities together." The excavations showed that the potters joined cooperatives that shared in the use of gigantic kilns with a diameter of up to 7 meters. The craftsmen's district in Selinunte probably stretched for more than 600 meters along the city walls and is thus among the largest ones known today. The excavations are in the hands of faculty and students from Bonn and Rome -- and they are exhausting. For excavations go on in August and September, when the heat reaches its peak -- but in exchange, there is very little rain.

"This work is a challenge for all involved," commented dig manager Bentz. "This is no camping trip." But for students, it is a great opportunity to learn archeological methods by doing. The Bonn researchers were surprised to find even older remnants of workshops under the 5th c. kilns. While these finds have not been completely excavated yet, indications are -- so the archeologists -- that pottery workshops existed in the same location during the city's early phase in the 6th century B.C. This means that craftsmen were probably intentionally housed on the edge as early as during the design of the city, which was -- like many colonies -- planned on the drawing board.

Reconstructing the past

The finds from the craftsmen's district are not exactly treasures, but they are still valuable for reconstructing the past. In the early phase, widely ranging finds of clay vessels, tiles and bronzes -- among them also imports from Athens and Sparta -- indicate that living and work quarters were housed together. Over the course of the 5th century, the two areas were separated increasingly.

"We hope to improve our understanding of that in future," said Prof. Bentz. But so far, he continued, little was known about the social conditions prevailing during the founding of a colony. What was certain is that often, it was hunger and need that drove settlers to emigrate and found a new city. Why and under what conditions some of them became potters, other farmers, and others yet rich landowners who could afford to participate in the Olympic games -- these are questions that the excavations can shed some light on.

_________________

References:

Science Daily. 2011. "Archeologists Discover Huge Ancient Greek Commercial Area On Island of Sicily". Science Daily. Posted: November 14, 2011. Available online: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/11/111114093411.htm

Led by Professor Dr. Martin Bentz, archeologists at the University of Bonn began unearthing one of Greek antiquity's largest craftsmen's quarters in the Greek colonial city of Selinunte (7th-3rd century B.C.) on the island of Sicily during two excavation campaigns in September 2010 and in the fall of 2011.

The project is conducted in collaboration with the Italian authorities and the German Archaeological Institute. Its goal is to study an area of daily life in ancient cities that has hitherto received little attention.

"To what extent the ancient Greeks already had something like 'commercial areas' has been a point of discussion in expert circles to this day," said Bonn archeologist Dr. Gabriel Zuchtriegel, a research associate who coordinates the Selinunte project together with Dr. Jon Albers from the Institut für Klassische Archäologie der Universität Bonn at the Chair of Prof. Dr. Martin Bentz. "A concentration of certain 'industries' and craftsmen in special districts does not only presuppose proactive planning; it is also based on a certain idea of how a city should best be organized -- from a practical as well as from a social and political point of view, e.g., who will be allowed to live and work where?" The University of Bonn excavations are now contributing to finding a new answer to such questions.

Huge kilns, used communally

Concentration in a certain city district applied primarily to potteries in Selinunte, which were massed on the edge of the settlement in the very shadow of the city wall. "Consequently, their smoke, stench and noise did not inconvenience the other inhabitants as much," explained Dr. Zuchtriegel. "At the same time, this allowed several craftsmen to use kilns and storage facilities together." The excavations showed that the potters joined cooperatives that shared in the use of gigantic kilns with a diameter of up to 7 meters. The craftsmen's district in Selinunte probably stretched for more than 600 meters along the city walls and is thus among the largest ones known today. The excavations are in the hands of faculty and students from Bonn and Rome -- and they are exhausting. For excavations go on in August and September, when the heat reaches its peak -- but in exchange, there is very little rain.

"This work is a challenge for all involved," commented dig manager Bentz. "This is no camping trip." But for students, it is a great opportunity to learn archeological methods by doing. The Bonn researchers were surprised to find even older remnants of workshops under the 5th c. kilns. While these finds have not been completely excavated yet, indications are -- so the archeologists -- that pottery workshops existed in the same location during the city's early phase in the 6th century B.C. This means that craftsmen were probably intentionally housed on the edge as early as during the design of the city, which was -- like many colonies -- planned on the drawing board.

Reconstructing the past

The finds from the craftsmen's district are not exactly treasures, but they are still valuable for reconstructing the past. In the early phase, widely ranging finds of clay vessels, tiles and bronzes -- among them also imports from Athens and Sparta -- indicate that living and work quarters were housed together. Over the course of the 5th century, the two areas were separated increasingly.

"We hope to improve our understanding of that in future," said Prof. Bentz. But so far, he continued, little was known about the social conditions prevailing during the founding of a colony. What was certain is that often, it was hunger and need that drove settlers to emigrate and found a new city. Why and under what conditions some of them became potters, other farmers, and others yet rich landowners who could afford to participate in the Olympic games -- these are questions that the excavations can shed some light on.

_________________

References:

Science Daily. 2011. "Archeologists Discover Huge Ancient Greek Commercial Area On Island of Sicily". Science Daily. Posted: November 14, 2011. Available online: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/11/111114093411.htm

Monday, November 28, 2011

Thanksgiving's Cultural Cousins

A little extra something.

Traditions celebrating the harvest bring families together around the world.

Autumn festivals, including American Thanksgiving, East Asian Mid-Autumn Festival and Jewish Sukkot, celebrate family and the Earth's bounty in similar ways despite cultural differences.

Of those three, Thanksgiving is the newcomer.

The Pilgrims celebrated a harvest festival with the Native Americans in 1621. And their ancient Anglo-Saxon ancestors also celebrated autumn harvest festivals.

"Our word 'harvest' is a direct reflex of the Old English, or Anglo-Saxon, word 'hærfest,' which ... only meant 'autumn.' By extension, the word came to refer to the fruits of the field, brought home for processing," John Niles, emeritus professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, Madison told Discovery News.

But Thanksgiving wasn't an official annual event until 1863 when president Abraham Lincoln proclaimed, "...set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens."

Thanksgiving was new, but may have had an ancient inspiration in Leviticus, a holy book to both Jews and Christians. In Leviticus 23:39, God commanded the ancient Israelites to observe the Feast of Booths, Sukkot in Hebrew, "after you have gathered the crops of the land."

"The Pilgrims were avid Bible readers and Thanksgiving may have been inspired by Sukkot," Miriam Rinn, communications manager for the Jewish Community Center Association, told Discovery News.

"Sukkot is certainly a harvest festival, but also has greater religious significance," said Rinn.

"Thanking God for food (after eating) is a mitzvah, a religious obligation. Like all other Mitzvoth it connects man with God and enhance[s] the spiritual proximity between the two, a sense of mutual love," Rabbi Yossi Feintuch of Congregation Beth Shalom in Columbia, Missouri told Discovery News.

During sukkot, celebrated this year from Oct. 12-19, observers worship, eat and even sleep in a sukkah, a flimsy booth representing the temporary structures the Israelites used after fleeing Egypt.

"You cannot appreciate ... protections availed by your home unless you experience being removed from these protections if only briefly and temporarily," said Feintuch.

"The sukkah also represents the transience and fragility of life," said Rinn.

The celebration of the Mid-Autumn, or Moon Festival in China, Taiwan, Vietnam and other East Asian countries, also involves food and family and friends.

"During the Mid-Autumn festival people come back home to be with their family. It's one of the biggest holidays," said Gene Cheung, multicultural coordinator of the Asian Affairs Center as the University of Missouri.

The tradition took on special significance for Cheung and his family in 1999, after an earthquake damaged their home in Nantou, Taiwan. They celebrated the Mid-Autumn Festival that year visiting with his father's five brothers and six sisters. This year the festival fell on Sept. 12.

And like Thanksgiving's turkey and cranberries, Cheung and his family look forward every year to a special harvest meal that includes the Mid-Autumn Festival moon cake. Traditional moon cakes are soft, sweet pastry with an egg yolk and red bean paste inside, said Cheung.

"When you cut them open, it looks like a half-moon," said Cheung.

The shorter days and longer nights of the harvest season bring about more opportunities to star-gaze and watch the phases of the moon.

_________________

Reference:

Wall, Tim. 2011. "Thanksgiving's Cultural Cousins". Discovery News. Posted: November 21, 2011. Available online: http://news.discovery.com/earth/thanksgivings-cultural-cousins-111121.html

Traditions celebrating the harvest bring families together around the world.

Autumn festivals, including American Thanksgiving, East Asian Mid-Autumn Festival and Jewish Sukkot, celebrate family and the Earth's bounty in similar ways despite cultural differences.

Of those three, Thanksgiving is the newcomer.

The Pilgrims celebrated a harvest festival with the Native Americans in 1621. And their ancient Anglo-Saxon ancestors also celebrated autumn harvest festivals.

"Our word 'harvest' is a direct reflex of the Old English, or Anglo-Saxon, word 'hærfest,' which ... only meant 'autumn.' By extension, the word came to refer to the fruits of the field, brought home for processing," John Niles, emeritus professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, Madison told Discovery News.

But Thanksgiving wasn't an official annual event until 1863 when president Abraham Lincoln proclaimed, "...set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens."

Thanksgiving was new, but may have had an ancient inspiration in Leviticus, a holy book to both Jews and Christians. In Leviticus 23:39, God commanded the ancient Israelites to observe the Feast of Booths, Sukkot in Hebrew, "after you have gathered the crops of the land."

"The Pilgrims were avid Bible readers and Thanksgiving may have been inspired by Sukkot," Miriam Rinn, communications manager for the Jewish Community Center Association, told Discovery News.

"Sukkot is certainly a harvest festival, but also has greater religious significance," said Rinn.

"Thanking God for food (after eating) is a mitzvah, a religious obligation. Like all other Mitzvoth it connects man with God and enhance[s] the spiritual proximity between the two, a sense of mutual love," Rabbi Yossi Feintuch of Congregation Beth Shalom in Columbia, Missouri told Discovery News.

During sukkot, celebrated this year from Oct. 12-19, observers worship, eat and even sleep in a sukkah, a flimsy booth representing the temporary structures the Israelites used after fleeing Egypt.

"You cannot appreciate ... protections availed by your home unless you experience being removed from these protections if only briefly and temporarily," said Feintuch.

"The sukkah also represents the transience and fragility of life," said Rinn.

The celebration of the Mid-Autumn, or Moon Festival in China, Taiwan, Vietnam and other East Asian countries, also involves food and family and friends.

"During the Mid-Autumn festival people come back home to be with their family. It's one of the biggest holidays," said Gene Cheung, multicultural coordinator of the Asian Affairs Center as the University of Missouri.

The tradition took on special significance for Cheung and his family in 1999, after an earthquake damaged their home in Nantou, Taiwan. They celebrated the Mid-Autumn Festival that year visiting with his father's five brothers and six sisters. This year the festival fell on Sept. 12.

And like Thanksgiving's turkey and cranberries, Cheung and his family look forward every year to a special harvest meal that includes the Mid-Autumn Festival moon cake. Traditional moon cakes are soft, sweet pastry with an egg yolk and red bean paste inside, said Cheung.

"When you cut them open, it looks like a half-moon," said Cheung.

The shorter days and longer nights of the harvest season bring about more opportunities to star-gaze and watch the phases of the moon.

_________________

Reference:

Wall, Tim. 2011. "Thanksgiving's Cultural Cousins". Discovery News. Posted: November 21, 2011. Available online: http://news.discovery.com/earth/thanksgivings-cultural-cousins-111121.html

Big, little, tall and tiny: Words that promote important spatial skills

Research shows learning words about size and shape improve readiness for STEM education

reschool children who hear parents use words describing the size and shape of objects and who then use those words in their day to day interactions do much better on tests of their spatial skills, a University of Chicago study shows.

The study is the first to demonstrate that learning to use a wide range of words related to shape and size may improve children's later spatial skills, which are important in mathematics, science and technology.

These are skills that physicists and engineers rely on to take an abstract idea, conceptualize it and turn it into a real-world process, action or device, for example.

Researchers found that 1- to 4-year-olds who heard and then spoke 45 additional spatial words that described sizes and shapes saw, on average, a 23 percent increase in their scores on a non-verbal assessment of spatial thinking.

"Our results suggest that children's talk about space early in development is a significant predictor of their later spatial thinking," said University of Chicago psychologist Susan Levine, an author of a paper published on the research in the current issue of Developmental Science.

Shannon Pruden of Florida International University and Janellen Huttenlocher, also of University of Chicago, coauthored the paper with her. A video interview with Levine about this research can be found on the University of Chicago website.

"In view of findings that show spatial thinking is an important predictor of STEM achievement and careers, it is important to explore the kinds of early inputs that are related to the development of thinking in this domain," Levine and colleagues write in the article, "Children's Spatial Thinking: Does Talk about the Spatial World Matter?"

STEM--Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics--education is seen as vitally important for the next generation of science and technology innovators in the 21st century. In fact, a 2007 report issued by the National Science Board argues that to succeed in a new information-based and highly technological society, all students need to develop their capabilities in STEM to levels much beyond what was considered acceptable in the past, and enhancing spatial thinking is an important component of achieving this goal.

"This study is important because it will help parents and caregivers to better recognize and to seek opportunities that enhance children's spatial learning," said Soo-Siang Lim, director for the Science of Learning Centers Program at the National Science Foundation, which partially funded the study. "Study results could also help spatial learning play a more purposeful role in children's learning trajectories."

For the study, the research team videotaped children between ages 14 and 46 months and their primary caregivers, who were mainly the children's mothers. Researchers videotaped the caregivers as they interacted with their children in 90 minute sessions at four-month intervals. Caregivers and children were asked to engage in their normal, everyday activities.

The study group included 52 children and 52 parents from an economically and ethnically diverse set of homes in the Chicago area.

The researchers recorded words that were related to spatial concepts used by both children and their parents. They noted the use of names for two and three dimensional objects, such as circle or triangle. They also noted words that described size, such as tall and wide and words descriptive of spatial features such as bent, edge and corner.

The researchers found a great variation in the number of spatial words used by parents. On average parents used 167 words related to spatial concepts, but the range was very wide with parents using from 5 to 525 spatial words.

Among children, there was a similar variability, with children producing an average of 74 spatial related words and using a range of 4 to 191 words during the study period--composed of nine, 90 minute visits. The children who used more spatial terms were more likely to have caregivers who used those terms more often.

Moreover, when the children were four and a half years old, the team tested them for their spatial skills, to see if they could mentally rotate objects, copy block designs or match analogous spatial relations.

The researchers found that the children who were exposed to more spatial terms as part of their everyday activities and learned to produce these words themselves did much better on spatial tests than children who did not hear and produce as many of these terms. Importantly, this was true even controlling for children's overall productive vocabulary.

The impact was biggest for two of the tasks--the spatial analogies task and the mental rotation task. On the spatial analogy task, children, ages four and a half, were shown an array of four pictures and asked to select which picture "goes best" with a target picture--the one that depicted the same spatial relation.

On this nonverbal spatial analogies matching test, for every 45 additional spatial words children produced during their spontaneous talk with their parents, researchers saw a 23 percent increase in scores. Children who produced 45 more spatial words saw a 15 percent increase on a separate test assessing their ability to mentally rotate shapes.

The increased use of spatial language may have prompted the children's attention to the depicted spatial relations and improved their ability to solve spatial problems, the researchers said. The language knowledge may also have reduced the mental load involved in transforming shapes on the mental rotation task, they added.

In addition to NSF's Science of Learning Centers Program award to the Spatial Intelligence and Learning Center, the research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

________________

References:

EurekAlert. 2011. "Big, little, tall and tiny: Words that promote important spatial skills". EurekAlert. Posted: November 9, 2011. Available online: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-11/nsf-blt110911.php

reschool children who hear parents use words describing the size and shape of objects and who then use those words in their day to day interactions do much better on tests of their spatial skills, a University of Chicago study shows.

The study is the first to demonstrate that learning to use a wide range of words related to shape and size may improve children's later spatial skills, which are important in mathematics, science and technology.

These are skills that physicists and engineers rely on to take an abstract idea, conceptualize it and turn it into a real-world process, action or device, for example.

Researchers found that 1- to 4-year-olds who heard and then spoke 45 additional spatial words that described sizes and shapes saw, on average, a 23 percent increase in their scores on a non-verbal assessment of spatial thinking.

"Our results suggest that children's talk about space early in development is a significant predictor of their later spatial thinking," said University of Chicago psychologist Susan Levine, an author of a paper published on the research in the current issue of Developmental Science.

Shannon Pruden of Florida International University and Janellen Huttenlocher, also of University of Chicago, coauthored the paper with her. A video interview with Levine about this research can be found on the University of Chicago website.

"In view of findings that show spatial thinking is an important predictor of STEM achievement and careers, it is important to explore the kinds of early inputs that are related to the development of thinking in this domain," Levine and colleagues write in the article, "Children's Spatial Thinking: Does Talk about the Spatial World Matter?"

STEM--Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics--education is seen as vitally important for the next generation of science and technology innovators in the 21st century. In fact, a 2007 report issued by the National Science Board argues that to succeed in a new information-based and highly technological society, all students need to develop their capabilities in STEM to levels much beyond what was considered acceptable in the past, and enhancing spatial thinking is an important component of achieving this goal.

"This study is important because it will help parents and caregivers to better recognize and to seek opportunities that enhance children's spatial learning," said Soo-Siang Lim, director for the Science of Learning Centers Program at the National Science Foundation, which partially funded the study. "Study results could also help spatial learning play a more purposeful role in children's learning trajectories."

For the study, the research team videotaped children between ages 14 and 46 months and their primary caregivers, who were mainly the children's mothers. Researchers videotaped the caregivers as they interacted with their children in 90 minute sessions at four-month intervals. Caregivers and children were asked to engage in their normal, everyday activities.

The study group included 52 children and 52 parents from an economically and ethnically diverse set of homes in the Chicago area.

The researchers recorded words that were related to spatial concepts used by both children and their parents. They noted the use of names for two and three dimensional objects, such as circle or triangle. They also noted words that described size, such as tall and wide and words descriptive of spatial features such as bent, edge and corner.

The researchers found a great variation in the number of spatial words used by parents. On average parents used 167 words related to spatial concepts, but the range was very wide with parents using from 5 to 525 spatial words.

Among children, there was a similar variability, with children producing an average of 74 spatial related words and using a range of 4 to 191 words during the study period--composed of nine, 90 minute visits. The children who used more spatial terms were more likely to have caregivers who used those terms more often.

Moreover, when the children were four and a half years old, the team tested them for their spatial skills, to see if they could mentally rotate objects, copy block designs or match analogous spatial relations.

The researchers found that the children who were exposed to more spatial terms as part of their everyday activities and learned to produce these words themselves did much better on spatial tests than children who did not hear and produce as many of these terms. Importantly, this was true even controlling for children's overall productive vocabulary.

The impact was biggest for two of the tasks--the spatial analogies task and the mental rotation task. On the spatial analogy task, children, ages four and a half, were shown an array of four pictures and asked to select which picture "goes best" with a target picture--the one that depicted the same spatial relation.

On this nonverbal spatial analogies matching test, for every 45 additional spatial words children produced during their spontaneous talk with their parents, researchers saw a 23 percent increase in scores. Children who produced 45 more spatial words saw a 15 percent increase on a separate test assessing their ability to mentally rotate shapes.

The increased use of spatial language may have prompted the children's attention to the depicted spatial relations and improved their ability to solve spatial problems, the researchers said. The language knowledge may also have reduced the mental load involved in transforming shapes on the mental rotation task, they added.

In addition to NSF's Science of Learning Centers Program award to the Spatial Intelligence and Learning Center, the research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

________________

References:

EurekAlert. 2011. "Big, little, tall and tiny: Words that promote important spatial skills". EurekAlert. Posted: November 9, 2011. Available online: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-11/nsf-blt110911.php

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Western perspectives mean that Aboriginal contemporary art is misunderstood

The Western art world interprets art from a Western perspective. Australian Aboriginal art is therefore often displayed in Stockholm's Museum of Ethnography, while in Australia it is regarded as contemporary art and is displayed in art museums and sold in galleries. This is shown in a thesis from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

In her research, Beatrice Persson questions what contemporary art actually is, and whether the global art world really is global. By studying how Australian contemporary art is defined by art historians, cultural experts and curators in Australia, she has been able to distinguish four categories within contemporary art in Australia. Two of these categories consist of Aboriginal art: so-called traditional Aboriginal art and city-based Aboriginal art.

"Traditional Aboriginal art is art that is created by Aboriginal artists who live traditionally and work in remote communities, in territories with a connection to their ancestors' creation stories, or Dreamings," she explains. "City-based Aboriginal art, on the other hand, is created by Aboriginal artists who live in urban environments and have studied at Western art schools."

The other two categories are "young" Australian art, which is created by young Australian artists, and Asian-Australian art, which is created by artists from Asia who have immigrated to Australia.

Persson then studied the four categories in relation to the concept of cross-culture, which is illustrated on the basis of how primitive art, and non-Western art in general, has been viewed since the end of the 19th century, revealing a history of colonialism in which culture clashes have made influences and changes possible within art, but where the Western World has had the power to decide what constitutes art, and contemporaneity or "simultaneousness", a concept that can be understood as an attempt to structure different artistic expressions that are created at the same time in different closely connected but mutually incomparable cultures.

"In my research I try to use these concepts to embrace both Western and non-Western art and art that crosses the divide between different cultures – art that can be said to depict the spirit of our times."

The results of this research show that the globalised art world is still lacking a non-Western interpretation perspective.

"The fact that this interpretation perspective is missing means that we are unable to understand the significance that non-Western art has in its native cultures. This makes it impossible for Western observers to understand and interpret this art on its own terms. And if we don't know what we're seeing when looking at art, how can we view it on the same terms as Western art?"

_________________

References:

EurekAlert. 2011. "Western perspectives mean that Aboriginal contemporary art is misunderstood". EurekAlert. Posted: November 8, 2011. Available online: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-11/uog-wpm110811.php

In her research, Beatrice Persson questions what contemporary art actually is, and whether the global art world really is global. By studying how Australian contemporary art is defined by art historians, cultural experts and curators in Australia, she has been able to distinguish four categories within contemporary art in Australia. Two of these categories consist of Aboriginal art: so-called traditional Aboriginal art and city-based Aboriginal art.

"Traditional Aboriginal art is art that is created by Aboriginal artists who live traditionally and work in remote communities, in territories with a connection to their ancestors' creation stories, or Dreamings," she explains. "City-based Aboriginal art, on the other hand, is created by Aboriginal artists who live in urban environments and have studied at Western art schools."

The other two categories are "young" Australian art, which is created by young Australian artists, and Asian-Australian art, which is created by artists from Asia who have immigrated to Australia.

Persson then studied the four categories in relation to the concept of cross-culture, which is illustrated on the basis of how primitive art, and non-Western art in general, has been viewed since the end of the 19th century, revealing a history of colonialism in which culture clashes have made influences and changes possible within art, but where the Western World has had the power to decide what constitutes art, and contemporaneity or "simultaneousness", a concept that can be understood as an attempt to structure different artistic expressions that are created at the same time in different closely connected but mutually incomparable cultures.

"In my research I try to use these concepts to embrace both Western and non-Western art and art that crosses the divide between different cultures – art that can be said to depict the spirit of our times."

The results of this research show that the globalised art world is still lacking a non-Western interpretation perspective.

"The fact that this interpretation perspective is missing means that we are unable to understand the significance that non-Western art has in its native cultures. This makes it impossible for Western observers to understand and interpret this art on its own terms. And if we don't know what we're seeing when looking at art, how can we view it on the same terms as Western art?"

_________________

References:

EurekAlert. 2011. "Western perspectives mean that Aboriginal contemporary art is misunderstood". EurekAlert. Posted: November 8, 2011. Available online: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-11/uog-wpm110811.php

Saturday, November 26, 2011

Through the Language Glass by Guy Deutscher – review

BOOK REVIEW

An exuberant book, rich in anecdote, instance and oddity, about the curious interactions between language and perception

In April 2002, the great journal Lloyd's List gave shipping a sex change, switching the nautical pronoun to "it". According to Guy Deutscher, "'she' fell by the quayside." There, in half a sentence, you have the delight of this book: pertinent anecdote, relaxed wit and an uneasy sense that the author is always one jump ahead.

In April 2002, the great journal Lloyd's List gave shipping a sex change, switching the nautical pronoun to "it". According to Guy Deutscher, "'she' fell by the quayside." There, in half a sentence, you have the delight of this book: pertinent anecdote, relaxed wit and an uneasy sense that the author is always one jump ahead.

As a reporter who once covered the waterfront, I loved Lloyd's List. Its closely printed pages recorded so much of the world's shipping traffic and its tragedies (in its berths and deaths columns, so to speak). But editorial fiat couldn't change the thinking of a generation that metaphorically pushed the boat out, or waited for their ship to come in; that caught the tide or sailed against the wind; that grew up with Captain Marryat, C S Forester and Joseph Conrad. To such people, English ships display feminine grace, not because a bulk carrier, barge or battleship is innately female, but because some linguistic convention ensured that for a thousand years after the Norman Conquest, the English language retained "she" for shipping even as it neutered almost every other inanimate thing, including trees.

Put like that, the logic is obvious: of course a language that confers masculinity on a pine tree but femininity on a palm would be able to play with imagery that might make no sense in translation to a language that did not. Deutscher's book begins with a promise to demolish the intellectual clichés, and subvert glib anecdotal demonstrations of the way our mother tongue defines or limits our thought, and then confirms that in very limited instances, it almost certainly does shape the way we see the world. The book is a joyous and unexpected intellectual journey through the strange interaction between language and the world that language attempts to describe.

At its heart is an old conundrum. Why was Homer's sea "wine-dark"? Did the Greeks have no word for blue? William Ewart Gladstone, already an ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer but not yet a prime minister, published in 1849 a 1,700-page, three-volume work on the poet of The Iliad and The Odyssey, and ended it with a chapter on Homer's perception and use of colour.

According to Deutscher, this profoundly affected "the development of at least three academic disciplines" and triggered a war over the linguistic link between culture and nature that, 150 years on, is still being fought. For Gladstone was inclined to think that because the Greek language offered such a limited visual palette, then perhaps colour perception had not evolved: perhaps ancient Greeks saw the world more in black and white than in Technicolour.

This hypothesis could – up to a point – be tested: perhaps other "primitive" cultures maintained the same handicap? Imperialist Europe and expansionist America were not short of subjects for research.

The question was: does not having a word for blue (or green) mean that people don't see that colour? Tests showed quickly enough that colour-blindness is not common, and is evenly distributed everywhere. So could there be something about the language that dictated a particular group's perception of or attention to colour? Or something about the demands of the local environment that necessarily shaped the tribal language?

The journey to a not-quite-cut-and-dried conclusion draws on history, ethnography and psychology as well as a little physiology, and delivers from the mix an exuberant book, rich in anecdote, instance and oddity. Great names flit across the pages; great stories, too, about the astonishing variety of human speech and the riches of even the most supposedly primitive, vanishing languages. The speakers of Guugu Yimithirr, for example, would never advise a motorist to take the second left: all their conversation is in exquisitely precise geographic coordinates. They even, says Deutscher, dream in cardinal directions.

This is a book written in blissful English, by someone whose mother tongue is Hebrew, who is an expert in near-Eastern languages and who can no doubt talk his way confidently around Europe and far beyond: a living rebuke to the obdurate Anglo-Saxon monoglot.

_______________

References:

Radford, Tim. 2011. "Through the Language Glass by Guy Deutscher – review". Guardian. Posted: November 8, 2011. Available online: http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2011/nov/08/through-language-glass-guy-deutscher-review

An exuberant book, rich in anecdote, instance and oddity, about the curious interactions between language and perception

In April 2002, the great journal Lloyd's List gave shipping a sex change, switching the nautical pronoun to "it". According to Guy Deutscher, "'she' fell by the quayside." There, in half a sentence, you have the delight of this book: pertinent anecdote, relaxed wit and an uneasy sense that the author is always one jump ahead.

In April 2002, the great journal Lloyd's List gave shipping a sex change, switching the nautical pronoun to "it". According to Guy Deutscher, "'she' fell by the quayside." There, in half a sentence, you have the delight of this book: pertinent anecdote, relaxed wit and an uneasy sense that the author is always one jump ahead.As a reporter who once covered the waterfront, I loved Lloyd's List. Its closely printed pages recorded so much of the world's shipping traffic and its tragedies (in its berths and deaths columns, so to speak). But editorial fiat couldn't change the thinking of a generation that metaphorically pushed the boat out, or waited for their ship to come in; that caught the tide or sailed against the wind; that grew up with Captain Marryat, C S Forester and Joseph Conrad. To such people, English ships display feminine grace, not because a bulk carrier, barge or battleship is innately female, but because some linguistic convention ensured that for a thousand years after the Norman Conquest, the English language retained "she" for shipping even as it neutered almost every other inanimate thing, including trees.

Put like that, the logic is obvious: of course a language that confers masculinity on a pine tree but femininity on a palm would be able to play with imagery that might make no sense in translation to a language that did not. Deutscher's book begins with a promise to demolish the intellectual clichés, and subvert glib anecdotal demonstrations of the way our mother tongue defines or limits our thought, and then confirms that in very limited instances, it almost certainly does shape the way we see the world. The book is a joyous and unexpected intellectual journey through the strange interaction between language and the world that language attempts to describe.

At its heart is an old conundrum. Why was Homer's sea "wine-dark"? Did the Greeks have no word for blue? William Ewart Gladstone, already an ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer but not yet a prime minister, published in 1849 a 1,700-page, three-volume work on the poet of The Iliad and The Odyssey, and ended it with a chapter on Homer's perception and use of colour.

According to Deutscher, this profoundly affected "the development of at least three academic disciplines" and triggered a war over the linguistic link between culture and nature that, 150 years on, is still being fought. For Gladstone was inclined to think that because the Greek language offered such a limited visual palette, then perhaps colour perception had not evolved: perhaps ancient Greeks saw the world more in black and white than in Technicolour.

This hypothesis could – up to a point – be tested: perhaps other "primitive" cultures maintained the same handicap? Imperialist Europe and expansionist America were not short of subjects for research.

The question was: does not having a word for blue (or green) mean that people don't see that colour? Tests showed quickly enough that colour-blindness is not common, and is evenly distributed everywhere. So could there be something about the language that dictated a particular group's perception of or attention to colour? Or something about the demands of the local environment that necessarily shaped the tribal language?

The journey to a not-quite-cut-and-dried conclusion draws on history, ethnography and psychology as well as a little physiology, and delivers from the mix an exuberant book, rich in anecdote, instance and oddity. Great names flit across the pages; great stories, too, about the astonishing variety of human speech and the riches of even the most supposedly primitive, vanishing languages. The speakers of Guugu Yimithirr, for example, would never advise a motorist to take the second left: all their conversation is in exquisitely precise geographic coordinates. They even, says Deutscher, dream in cardinal directions.

This is a book written in blissful English, by someone whose mother tongue is Hebrew, who is an expert in near-Eastern languages and who can no doubt talk his way confidently around Europe and far beyond: a living rebuke to the obdurate Anglo-Saxon monoglot.

_______________

References:

Radford, Tim. 2011. "Through the Language Glass by Guy Deutscher – review". Guardian. Posted: November 8, 2011. Available online: http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2011/nov/08/through-language-glass-guy-deutscher-review

Friday, November 25, 2011

Castles in the desert - satellites reveal lost cities of Libya

Fall of Gaddafi lifts the veil on archaeological treasures

Satellite imagery has uncovered new evidence of a lost civilization of the Sahara in Libya's south-western desert wastes that will help re-write the history of the country.

The fall of Gaddafi has opened the way for archaeologists to explore the country's pre-Islamic heritage, so long ignored under his regime.

Using satellites and air-photographs to identify the remains in one of the most inhospitable parts of the desert, a British team has discovered more than 100 fortified farms and villages with castle-like structures and several towns, most dating between AD 1-500.

These "lost cities" were built by a little-known ancient civilisation called the Garamantes, whose lifestyle and culture was far more advanced and historically significant than the ancient sources suggested.

The team from the University of Leicester has identified the mud brick remains of the castle-like complexes, with walls still standing up to four metres high, along with traces of dwellings, cairn cemeteries, associated field systems, wells and sophisticated irrigation systems. Follow-up ground survey earlier this year confirmed the pre-Islamic date and remarkable preservation.

"It is like someone coming to England and suddenly discovering all the medieval castles. These settlements had been unremarked and unrecorded under the Gaddafi regime," says the project leader David Mattingly FBA, Professor of Roman Archaeology at the University of Leicester.

"Satellite imagery has given us the ability to cover a large region. The evidence suggests that the climate has not changed over the years and we can see that this inhospitable landscape with zero rainfall was once very densely built up and cultivated. These are quite exceptional ancient landscapes, both in terms of the range of features and the quality of preservation," says Dr Martin Sterry, also of the University of Leicester, who has been responsible for much of the image analysis and site interpretation.

The findings challenge a view dating back to Roman accounts that the Garamantes consisted of barbaric nomads and troublemakers on the edge of the Roman Empire.

"In fact, they were highly civilised, living in large-scale fortified settlements, predominantly as oasis farmers. It was an organised state with towns and villages, a written language and state of the art technologies. The Garamantes were pioneers in establishing oases and opening up Trans-Saharan trade," Professor Mattingly said.

The professor and his team were forced to evacuate Libya in February when the anti-Gaddafi revolt started, but hope to be able to return to the field as soon as security is fully restored. The Libyan antiquities department, badly under-resourced under Gaddafi, is closely involved in the project. Funding for the research has come from the European Research Council who awarded Professor Mattingly an ERC Advanced Grant of nearly 2.5m euros, the Leverhulme Trust, the Society for Libyan Studies and the GeoEye Foundation.

"It is a new start for Libya's antiquities service and a chance for the Libyan people to engage with their own long-suppressed history," says Professor Mattingly.

"These represent the first towns in Libya that weren't the colonial imposition of Mediterranean people such as the Greeks and Romans. The Garamantes should be central to what Libyan school children learn about their history and heritage."

_________________

References:

EurekAlert. 2011. "Castles in the desert - satellites reveal lost cities of Libya". EurekAlert. Posted: November 7, 2011. Available online: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-11/uol-cit110711.php

Satellite imagery has uncovered new evidence of a lost civilization of the Sahara in Libya's south-western desert wastes that will help re-write the history of the country.

The fall of Gaddafi has opened the way for archaeologists to explore the country's pre-Islamic heritage, so long ignored under his regime.

Using satellites and air-photographs to identify the remains in one of the most inhospitable parts of the desert, a British team has discovered more than 100 fortified farms and villages with castle-like structures and several towns, most dating between AD 1-500.

These "lost cities" were built by a little-known ancient civilisation called the Garamantes, whose lifestyle and culture was far more advanced and historically significant than the ancient sources suggested.

The team from the University of Leicester has identified the mud brick remains of the castle-like complexes, with walls still standing up to four metres high, along with traces of dwellings, cairn cemeteries, associated field systems, wells and sophisticated irrigation systems. Follow-up ground survey earlier this year confirmed the pre-Islamic date and remarkable preservation.

"It is like someone coming to England and suddenly discovering all the medieval castles. These settlements had been unremarked and unrecorded under the Gaddafi regime," says the project leader David Mattingly FBA, Professor of Roman Archaeology at the University of Leicester.

"Satellite imagery has given us the ability to cover a large region. The evidence suggests that the climate has not changed over the years and we can see that this inhospitable landscape with zero rainfall was once very densely built up and cultivated. These are quite exceptional ancient landscapes, both in terms of the range of features and the quality of preservation," says Dr Martin Sterry, also of the University of Leicester, who has been responsible for much of the image analysis and site interpretation.

The findings challenge a view dating back to Roman accounts that the Garamantes consisted of barbaric nomads and troublemakers on the edge of the Roman Empire.

"In fact, they were highly civilised, living in large-scale fortified settlements, predominantly as oasis farmers. It was an organised state with towns and villages, a written language and state of the art technologies. The Garamantes were pioneers in establishing oases and opening up Trans-Saharan trade," Professor Mattingly said.

The professor and his team were forced to evacuate Libya in February when the anti-Gaddafi revolt started, but hope to be able to return to the field as soon as security is fully restored. The Libyan antiquities department, badly under-resourced under Gaddafi, is closely involved in the project. Funding for the research has come from the European Research Council who awarded Professor Mattingly an ERC Advanced Grant of nearly 2.5m euros, the Leverhulme Trust, the Society for Libyan Studies and the GeoEye Foundation.

"It is a new start for Libya's antiquities service and a chance for the Libyan people to engage with their own long-suppressed history," says Professor Mattingly.

"These represent the first towns in Libya that weren't the colonial imposition of Mediterranean people such as the Greeks and Romans. The Garamantes should be central to what Libyan school children learn about their history and heritage."

_________________

References:

EurekAlert. 2011. "Castles in the desert - satellites reveal lost cities of Libya". EurekAlert. Posted: November 7, 2011. Available online: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-11/uol-cit110711.php

Thursday, November 24, 2011

How to Shrink a Head

Don't try this at home!

__________________

References:

Live Science. 2011. "How to Shrink a Head". Live Science. Posted: N/D. Available online: http://www.livescience.com/16936-shrink-head.html

__________________

References:

Live Science. 2011. "How to Shrink a Head". Live Science. Posted: N/D. Available online: http://www.livescience.com/16936-shrink-head.html

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Scientists Find Evidence of Ancient Megadrought in Southwestern U.S.

A new study at the University of Arizona's Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research has revealed a previously unknown multi-decade drought period in the second century A.D. The findings give evidence that extended periods of aridity have occurred at intervals throughout our past.

Almost 900 years ago, in the mid-12th century, the southwestern U.S. was in the middle of a multi-decade megadrought. It was the most recent extended period of severe drought known for this region. But it was not the first.

The second century A.D. saw an extended dry period of more than 100 years characterized by a multi-decade drought lasting nearly 50 years, says a new study from scientists at the University of Arizona.

UA geoscientists Cody Routson, Connie Woodhouse and Jonathan Overpeck conducted a study of the southern San Juan Mountains in south-central Colorado. The region serves as a primary drainage site for the Rio Grande and San Juan rivers.

"These mountains are very important for both the San Juan River and the Rio Grande River," said Routson, a doctoral candidate in the environmental studies laboratory of the UA's department of geosciences and the primary author of the study, which is upcoming in Geophysical Research Letters.

The San Juan River is a tributary for the Colorado River, meaning any climate changes that affect the San Juan drainage also likely would affect the Colorado River and its watershed. Said Routson: "We wanted to develop as long a record as possible for that region."

Dendrochronology is a precise science of using annual growth rings of trees to understand climate in the past. Because trees add a normally clearly defined growth ring around their trunk each year, counting the rings backwards from a tree's bark allows scientists to determine not only the age of the tree, but which years were good for growth and which years were more difficult.

"If it's a wet year, they grow a wide ring, and if it's a dry year, they grow a narrow ring," said Routson. "If you average that pattern across trees in a region you can develop a chronology that shows what years were drier or wetter for that particular region."

Darker wood, referred to as latewood because it develops in the latter part of the year at the end of the growing season, forms a usually distinct boundary between one ring and the next. The latewood is darker because growth at the end of the growing season has slowed and the cells are more compact.

To develop their chronology, the researchers looked for indications of climate in the past in the growth rings of the oldest trees in the southern San Juan region. "We drove around and looked for old trees," said Routson.

Literally nothing is older than a bristlecone pine tree: The oldest and longest-living species on the planet, these pine trees normally are found clinging to bare rocky landscapes of alpine or near-alpine mountain slopes. The trees, the oldest of which are more than 4,000 years old, are capable of withstanding extreme drought conditions.

"We did a lot of hiking and found a couple of sites of bristlecone pines, and one in particular that we honed in on," said Routson.

To sample the trees without damaging them, the dendrochronologists used a tool like a metal screw that bores a tiny hole in the trunk of the tree and allows them to extract a sample, called a core. "We take a piece of wood about the size and shape of a pencil from the tree," explained Routson.

"We also sampled dead wood that was lying about the land. We took our samples back to the lab where we used a visual, graphic technique to match where the annual growth patterns of the living trees overlap with the patterns in the dead wood. Once we have the pattern matched we measure the rings and average these values to generate a site chronology."

"In our chronology for the south San Juan mountains we created a record that extends back 2,200 years," said Routson. "It was pretty profound that we were able to get back that far."

The chronology extends many years earlier than the medieval period, during which two major drought events in that region already were known from previous chronologies.

"The medieval period extends roughly from 800 to 1300 A.D.," said Routson. "During that period there was a lot of evidence from previous studies for increased aridity, in particular two major droughts: one in the middle of the 12th century, and one at the end of the 13th century."

"Very few records are long enough to assess the global conditions associated with these two periods of Southwestern aridity," said Routson. "And the available records have uncertainties."

But the chronology from the San Juan bristlecone pines showed something completely new:

"There was another period of increased aridity even earlier," said Routson. "This new record shows that in addition to known droughts from the medieval period, there is also evidence for an earlier megadrought during the second century A.D."

"What we can see from our record is that it was a period of basically 50 consecutive years of below-average growth," said Routson. "And that's within a much broader period that extends from around 124 A.D. to 210 A.D. -- about a 100-year-long period of dry conditions."

"We're showing that there are multiple extreme drought events that happened during our past in this region," said Routson. "These megadroughts lasted for decades, which is much longer than our current drought. And the climatic events behind these previous dry periods are really similar to what we're experiencing today."

The prolonged drought in the 12th century and the newly discovered event in the second century A.D. may both have been influenced by warmer-than-average Northern Hemisphere temperatures, Routson said: "The limited records indicate there may have been similar La Nina-like background conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean, which are known to influence modern drought, during the two periods."

Although natural climate variation has led to extended dry periods in the southwestern U.S. in the past, there is reason to believe that human-driven climate change will increase the frequency of extreme droughts in the future, said Routson. In other words, we should expect similar multi-decade droughts in a future predicted to be even warmer than the past.

Routson's research is funded by fellowships from the National Science Foundation, the Science Foundation Arizona and the Climate Assessment of the Southwest. His advisors, Woodhouse of the School of Geography and Development and Overpeck of the department of geosciences and co-director of the UA's Institute of the Environment, are co-authors of the study.

___________________

References:

Science Daily. 2011. "Scientists Find Evidence of Ancient Megadrought in Southwestern U.S.". Science Daily. Posted: November 6, 2011. Available online: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/11/111106151505.htm

Almost 900 years ago, in the mid-12th century, the southwestern U.S. was in the middle of a multi-decade megadrought. It was the most recent extended period of severe drought known for this region. But it was not the first.

The second century A.D. saw an extended dry period of more than 100 years characterized by a multi-decade drought lasting nearly 50 years, says a new study from scientists at the University of Arizona.

UA geoscientists Cody Routson, Connie Woodhouse and Jonathan Overpeck conducted a study of the southern San Juan Mountains in south-central Colorado. The region serves as a primary drainage site for the Rio Grande and San Juan rivers.

"These mountains are very important for both the San Juan River and the Rio Grande River," said Routson, a doctoral candidate in the environmental studies laboratory of the UA's department of geosciences and the primary author of the study, which is upcoming in Geophysical Research Letters.

The San Juan River is a tributary for the Colorado River, meaning any climate changes that affect the San Juan drainage also likely would affect the Colorado River and its watershed. Said Routson: "We wanted to develop as long a record as possible for that region."

Dendrochronology is a precise science of using annual growth rings of trees to understand climate in the past. Because trees add a normally clearly defined growth ring around their trunk each year, counting the rings backwards from a tree's bark allows scientists to determine not only the age of the tree, but which years were good for growth and which years were more difficult.

"If it's a wet year, they grow a wide ring, and if it's a dry year, they grow a narrow ring," said Routson. "If you average that pattern across trees in a region you can develop a chronology that shows what years were drier or wetter for that particular region."

Darker wood, referred to as latewood because it develops in the latter part of the year at the end of the growing season, forms a usually distinct boundary between one ring and the next. The latewood is darker because growth at the end of the growing season has slowed and the cells are more compact.

To develop their chronology, the researchers looked for indications of climate in the past in the growth rings of the oldest trees in the southern San Juan region. "We drove around and looked for old trees," said Routson.

Literally nothing is older than a bristlecone pine tree: The oldest and longest-living species on the planet, these pine trees normally are found clinging to bare rocky landscapes of alpine or near-alpine mountain slopes. The trees, the oldest of which are more than 4,000 years old, are capable of withstanding extreme drought conditions.

"We did a lot of hiking and found a couple of sites of bristlecone pines, and one in particular that we honed in on," said Routson.

To sample the trees without damaging them, the dendrochronologists used a tool like a metal screw that bores a tiny hole in the trunk of the tree and allows them to extract a sample, called a core. "We take a piece of wood about the size and shape of a pencil from the tree," explained Routson.

"We also sampled dead wood that was lying about the land. We took our samples back to the lab where we used a visual, graphic technique to match where the annual growth patterns of the living trees overlap with the patterns in the dead wood. Once we have the pattern matched we measure the rings and average these values to generate a site chronology."

"In our chronology for the south San Juan mountains we created a record that extends back 2,200 years," said Routson. "It was pretty profound that we were able to get back that far."

The chronology extends many years earlier than the medieval period, during which two major drought events in that region already were known from previous chronologies.

"The medieval period extends roughly from 800 to 1300 A.D.," said Routson. "During that period there was a lot of evidence from previous studies for increased aridity, in particular two major droughts: one in the middle of the 12th century, and one at the end of the 13th century."

"Very few records are long enough to assess the global conditions associated with these two periods of Southwestern aridity," said Routson. "And the available records have uncertainties."

But the chronology from the San Juan bristlecone pines showed something completely new:

"There was another period of increased aridity even earlier," said Routson. "This new record shows that in addition to known droughts from the medieval period, there is also evidence for an earlier megadrought during the second century A.D."

"What we can see from our record is that it was a period of basically 50 consecutive years of below-average growth," said Routson. "And that's within a much broader period that extends from around 124 A.D. to 210 A.D. -- about a 100-year-long period of dry conditions."

"We're showing that there are multiple extreme drought events that happened during our past in this region," said Routson. "These megadroughts lasted for decades, which is much longer than our current drought. And the climatic events behind these previous dry periods are really similar to what we're experiencing today."

The prolonged drought in the 12th century and the newly discovered event in the second century A.D. may both have been influenced by warmer-than-average Northern Hemisphere temperatures, Routson said: "The limited records indicate there may have been similar La Nina-like background conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean, which are known to influence modern drought, during the two periods."

Although natural climate variation has led to extended dry periods in the southwestern U.S. in the past, there is reason to believe that human-driven climate change will increase the frequency of extreme droughts in the future, said Routson. In other words, we should expect similar multi-decade droughts in a future predicted to be even warmer than the past.

Routson's research is funded by fellowships from the National Science Foundation, the Science Foundation Arizona and the Climate Assessment of the Southwest. His advisors, Woodhouse of the School of Geography and Development and Overpeck of the department of geosciences and co-director of the UA's Institute of the Environment, are co-authors of the study.

___________________

References:

Science Daily. 2011. "Scientists Find Evidence of Ancient Megadrought in Southwestern U.S.". Science Daily. Posted: November 6, 2011. Available online: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/11/111106151505.htm

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Fall of Gaddafi opens a new era for the Sahara's lost civilisation

Libyan leader showed no interest in ancient culture of Garamantes, but now archaeologists hope to unearth neglected slice of history

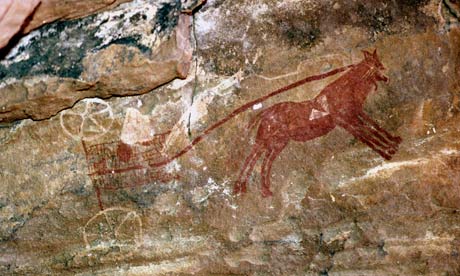

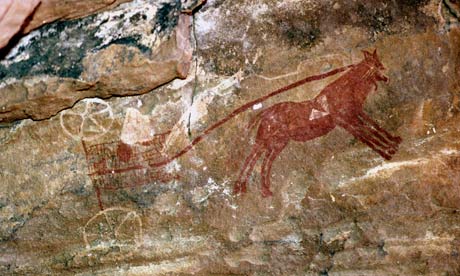

A painting, thought to show a Garamantes war chariot, found in southern Algeria. Photograph: Robert Estall/Alamy

The late Muammar Gaddafi was fond of insisting on the links between his republic and sub-Saharan Africa. He was less interested, however, in celebrating the black African civilisation that flourished for more than 1,500 years within what are now Libya's borders, and that was barely acknowledged in the Gaddafi-era curriculum.

Now, however, researchers into the Garamantes – a "lost" Saharan civilisation that flourished long before the Islamic era – are hoping that Libya's new government can restore the warrior culture, mentioned by Herodotus in his Histories, to its rightful place in Libya's history.

For while the impressive Roman ruins at Sabratha and Leptis Magna – both world heritage sites – are rightly famous, Libya's other cultural heritage, one that coexisted with its Roman settlers, has been largely forgotten.

It has been prompted by new research – including through the use of satellite imaging – which suggests that the Garamantes built more extensively and spread their culture more widely than previously thought.

The research has confirmed the view of Herodotus –not always the most reliable of chroniclers of his world, often supplying a good yarn when hard facts were hard to come by – that the Garmantes were a "very great nation".

Inhabiting an area around the busiest of the ancient trans-Saharan crossroads, the Garamantes were settled around three parallel areas of oases known today as the Wadi al-Ajal, the Wadi ash-Shati and the Zuwila-Murzuq-Burjuj depression with its capital at Jarmah.

They were tenacious builders of underground tunnels like Gaddafi. But while Gaddafi dug down to build huge complex bunkers, the Garamantes mined fossil water with which to irrigate their crops.

The Garamantes relied heavily on labour from sub-Saharan Africa, in the shape of slaves, to underpin their civilisation. Indeed, it is believed that they traded slaves as a commodity in exchange for the luxury goods that they imported in return.

Describing the recent finds as "extraordinary" in a paper co-authored for the journal Libyan Studies, Professor David Mattingly of the University of Leicester argues that the discoveries demonstrate that substantial trade across the Sahara long pre-dated the Islamic era.

Despite the increasing awareness of the importance of Libya's long-lost civilisation, Gaddafi was not much interested in these developments.

"We know that the material we produced for the Libyans ended up on Gaddafi's desk," said Mattingly, who has spent much of the last decade researching the archaeology of the Garamantes.

"But nothing ever happened. He wasn't interested and there was no mention of the Garamantes in the Libyan school curriculum."

All this, Mattingly hopes, will change amid emerging new evidence of both the scale and importance of the Garamantes' civilisation.

Occupying an area of some 250,000 square miles, the Garamantes, whom Herodotus described colourfully as herding cattle that "grazed backwards" and hunting Ethiopians from their chariots, are now known to have practised a sophisticated form of agriculture, occupying villages set around square forts or qasrs.

The very existence of the desert culture, however, was based on their use of underground water extraction tunnels – known as foggara in Berber, one of the peoples from whom the Garamantes were descended – whose construction was highly labour-intensive, requiring the acquisition of large numbers of slaves.

The Garamantian civilisation was unique. Its foundation is believed to have marked the first time in history when a riverless area of a major desert was settled by a complex urban society which planned its towns and imported luxury goods.

Indeed the sophistication of Garamantian building design – not least of its fortifications – may have been copied by the Romans, some of whose forts in north Africa are strikingly similar in appearance.

"Our latest work using satellite technology has identified hundreds of new villages and towns. It is pretty breathtaking," said Mattingly.

"The important thing to realise is that this was an urban and sedentary agricultural culture that existed in the middle of the Sahara.

"Uncovering the extent of it is like stumbling across the network of English medieval castles today. We know that the Garamantes traded. There were caravans of hundreds of camels every year."

Mattingly believes that, if the Garamantes' place in African history was under-recorded by the ancients, despite being mentioned by both Tacitus and Pliny, it is explicable by a Romano-centric colonial view of ancient history that persisted.

And while Mattingly's research has benefited from satellite imagery commissioned by the oil industry for exploration which has become available to academics, he is concerned that as Libya opens up again after its war – to tourism, building development and oil extraction – important Garamatian sites will need to be protected.

During the Nato air war against Gaddafi, Mattingly and his fellow researchers supplied coordinates of key archaeological sites to protect them from bomb damage.

So what happened to the Garamantes? In the end, like the Easter Islanders, the Anasazi, the Greenland Norse and the Maya – all civilisations whose downfall was studied by Jared Diamond in his book Collapse – it appears the Garamantes outgrew their ability to exploit the environment around them.

In the six centuries that they thrived, the Garamantes extracted, it is estimated, in the region of 30 billion gallons of water through the foggara system of subterranean tunnels.

In about the fourth century, however, the water started to run out, and to have dug deeper and further in search of it required more slaves than the Garamantes' military power could successfully deliver.

They reached what might be called a "peak water" moment. When they had passed peak water, the Garamantes – the "very great nation" — were doomed to decline.

___________________

References:

Beaumont, Peter. 2011. "Fall of Gaddafi opens a new era for the Sahara's lost civilisation". Guardian. Posted: November 5, 2011. Available online: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/nov/05/gaddafi-sahara-lost-civilisation-garamantes

A painting, thought to show a Garamantes war chariot, found in southern Algeria. Photograph: Robert Estall/Alamy